Generating relocatable code for ARM processors

Abstract

By upgrading the LLVM compiler, we solved the problem when neither LLVM nor the GCC could create the correct Position Independent Code for Cortex M controllers, with the code running in Flash memory rather than in RAM. Now the binary image of the program can be flashed to an arbitrary address and run from it, without being moved to another place.

Updating the microcontroller’s “firmware” is a dangerous process. Before, any hardware failure during the update could brick your device. Nowadays, devices usually have their own boot loader which lets you restart the update before your device’s functionality is lost. Until the update is not complete the device will not work. The fanciest way to update is to use two separate regions for the “firmware” – the main region and the reserve region. In the picture below, they are marked by red and blue accordingly. Initially, the red region is active, while the update will be loaded into the blue region. This way boot failure is not a big deal. The red region will still be running everything. And if the update is successful, the blue region will become active. The next update will be loaded into the red region, and so on. Each update will lead to this switch.

Unfortunately, with Cortex M systems such an approach cannot be used directly. The program is tied to absolute addresses and cannot be run in an arbitrary place. This article explains why that is the case and how we made the program relocatable by modifying the LLVM compiler.

Introduction

Someone who has read the documentation may say that compilers already have options to create relocatable code. In the case of LLVM it is -fropi, -frwpi and others. That is where we started our tests too. It turned out that these options were very convenient for the systems where the program was loaded entirely into RAM. In this case, both constants (which were located in the code) and variables (which were located in the data section) were located in the same big segment. This is why it could be easily moved within the RAM.

For Cortex M controllers it was not that easy. Their code was located in a high-volume ROM while the data was stored in a low-volume RAM. In addition, those entities were located in different parts of the Flash/RAM.

Use of these options led to either the data being shifted by the same offset as the program… But RAM was much smaller than ROM! Thus, data went out of the allowed bounds.

Or to a huge table of pointers to the code constants being created in RAM. The size of this table significantly raised the amount of used RAM. Therefore, sometimes the amount of RAM provided by Cortex M controllers was just not enough.

It became clear that for the target platform (Cortex M controllers) we had to make changes to the compiler.

Basic Principles

To keep things coherent, let’s start with the basics. In computers, data and code are located in the global memory. In the given architecture (just like with almost all other architectures) a linear address space is used, so the location of an object can be defined by a number. In order to perform a certain operation with a memory cell, the processor must know the address of this cell.

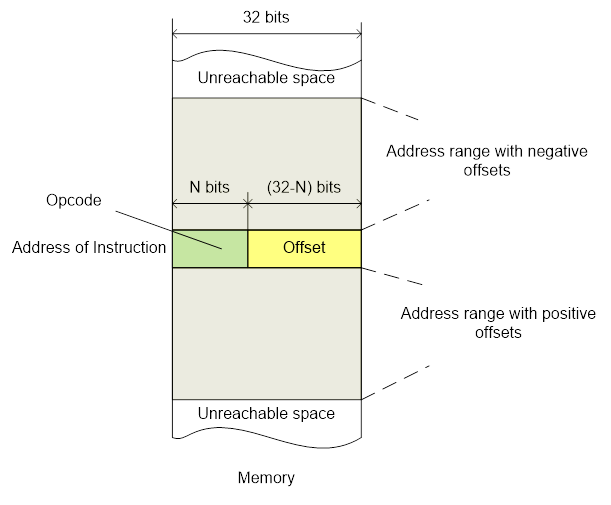

This is where things became complicated. Both maximum instruction and address sizes are 32 bits. Therefore, you could not just emplace 32-bit address into instruction – it had to have enough space for the instruction’s code. One of the solutions was to use relative addressing. At runtime, the program counter register contained the address of the current instruction. That was a full-size 32-bit register the contents of which was being controlled by the hardware. By reading it the program could know its own location in the Flash. There was enough space within the instruction for some offset, so a significant range of addresses around the current location became available. For example, if you needed to call a function that was located near the currently running function, the processor performed a jump with one instruction.

Here, function MyFunc is located near the call location:

bl MyFunc

...

.type MyFunc,%function

MyFunc:

...

However, it was only a partial solution, because not all jumps were relative, some were absolute. There was a solution though. We put the absolute address into the Flash directly within the code, somewhere near the place where it was being used. Then in a similar fashion, we performed a PC-relative load of this address into a register and loaded the value itself relative to the register with the next command. A more advanced method was to use a movw, movt instruction pair. The target 32-bit address was cut into two halves which was loaded into the register in two steps. Although it meant using two commands, it led to saving extra addressing.

Loading the contents of global_result_data7 address into the r0 register:

movw r0, :lower16:global_result_data7

movt r0, :upper16:global_result_data7

ldr r0, [r0]

Let’s take a closer look at the register loading process, where the variable global_result_data7 had the address 0x12345678:

Now, when we figured out how the processor operated with the addresses, it is time to explain where they come from. The Flash/RAM is (with some exceptions) uniform, which means that the function with the address 0x1000 may as well be located at the 0x2000, the only requirement is for the address to be known. The linker is responsible for address assignment. It receives all objects of the program as input and allocates space for them according to the attached configuration file. This way, every object gets its own address, and these addresses are written down to where the functions are being used. Moreover, it is worth noting that Flash/RAM does not have to start from the zero address, the starting address 0x08000000 is quite common as well. This value must be added to all global addresses.

Problem Definition

So, we had a binary image, suitable for loading into the device’s Flash/RAM. When we wrote it from the initial address defined at linking time and then ran it, the program worked. All data was located in the expected places, all the called addresses had the necessary functions, and so on. One may wonder, what if we had loaded the image from a different address? The first thing that comes to mind – everything would have fallen apart. The program would have accessed the cell value from the address 0x1000, but it would be actually located in a completely different place. However, let’s imagine a basic program consisting of only one instruction – infinite loop. Obviously, such a program was quite relocatable: and because such a short jump was performed PC-relatively, it automatically “adjusted” to its new location. Moreover, if all jumps/calls in the program were relative, it could be quite big and complex; at least all functions were called correctly. Everything was fine until the program tried to use a global address with a value that was offset relative to the expectations.

Now it is time to ask a question: was it an issue? What’s wrong with the program being tied to absolute addresses? What’s the benefit of a program that can run from an arbitrary address? One can argue that it is a good thing if it is cost-effective. Still it could have a much more specific use. For example, the device could receive a code snippet from the outside, which would expand the features of the already existing program, and load it as an addition to the current code. It would be very convenient if this code could work regardless of its location in the Flash. Lastly, there would be a possibility of a complete firmware update release. It also had to be located somewhere in the Flash and then given control of the device. Notably, we do not know where it ends up, so the ability to run from arbitrary addresses is a necessity.

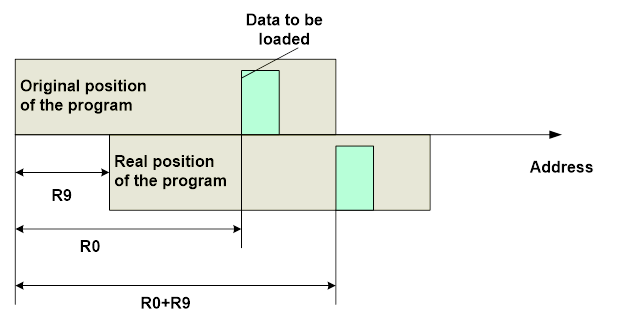

Therefore, the task of achieving relocatable code is worth looking into. It should be noted that in serious systems it is solved by using virtual memory. Logical addresses used in the program are silently mapped to physical addresses, so there are no problems. However, it is a completely different technological level. We were focused on the Cortex-M, without the MMU module. This is why in our case we had to “adjust” the global addresses by adding a program’s memory offset value. Because all address calculations came down to offsets and the difference of pointers, no other changes were required.

It brought up a new task – to retrieve the program’s offset value in the Flash relative to its initial address that was defined at linking time. For example, one could use the following trick. Global addresses remained the same, while the PC value was different. You got the difference between a global address and a PC one during run from a “normal address” and “hardcoded” it into the program. When run from an offset address this difference was different, and calculating how much it had changed gave you the offset value. However, as it will be shown later, there is a more direct way to get the offset value, so for now, let’s just say that the offset value is known.

Implementation (Initial Approach)

So, the processor loaded the global address into the register. When you use assembler, you only have to insert a specific instruction right after it, which will add the offset value to the result.

DoOperation function receives the global address global_operation5, which is modified by a r9 register value:

movw r0, :lower16:global_operation5

movt r0, :upper16:global_operation5

add r0, r9

bl DoOperation

To do this, we had to reserve the register for permanent storage of this value. Certainly, we could load it from RAM each time, but expected losses (ROM volume and processor cycles) were higher than if we were to lose one register. But what should we do if we coded in C? Obviously, the whole scheme only made sense when we did not have to modify the source code. It’s one thing to make some special manipulations here and there, but no major changes are allowed. Fortunately, the compiler could deal with the given task with only a minor modification.

The thing is, the compiler knows perfectly well what exactly it is doing. We used LLVM because we had extensive experience in modifying this compiler, so going forward we will discuss LLVM only. LLVM has a mechanism for separate address space which allows us to bind an attribute to a pointer, which defines data location. In our case, we assumed that only ROM content was moved, while RAM addresses stayed the same. In this case, we set a separate address space for constant global objects (functions, constant data, string literals – everything that went into the read-only memory).

Here we set a separate address space for constant data and map it to global objects:

llvm::Optional<LangAS> ARMTargetInfo::getConstantAddressSpace() const {

return getLangASFromTargetAS(REL_ROM_AS);

}

LangAS getGlobalVarAddressSpace(CodeGenModule &CGM, const VarDecl *D) const override {

if (D && CGM.isTypeConstant(D->getType(), false)) {

auto ConstAS = CGM.getTarget().getConstantAddressSpace();

assert(ConstAS && "No const AddressSpace");

return ConstAS.getValue();

}

return TargetCodeGenInfo::getGlobalVarAddressSpace(CGM, D);

}

This attribute “lived” inside the type during the whole compilation; during object address loading there was a way to recognize the ROM allocation and insert the instructions necessary for the offset.

Static Initialization Issue

Unfortunately, there was a scenario that we could not process with the given method. We had a global pointer array, which was initialized with a mix of ROM and RAM addresses.

Array arr contains two addresses: for ROM and for RAM:

int ro;

const int rw;

const int *arr[] = { &ro, &rw };

This initialization was performed statically, which meant that the linker allocated Flash and filled it with numbers, which were represented as symbolic addresses.

Static initialization of array arr:

.type arr,%object

.section .rodata,"a",%progbits

arr:

.long ro

.long rw

.size arr, 8

It did not know the future offset value yet, so it could not do anything. It shall be noted that linkers come in all shapes and sized, they can have various advanced features, but for that time, we stuck to simple binary images. So, we had an array of numbers. Still we could do nothing at runtime as well, because we did not know which addresses were from ROM and which were from RAM anymore. So, did our whole idea just go down the drain?

Essentially, there was a very costly but quite versatile solution. If we had known the RAM and ROM address ranges, we could have sent the whole addressing through a special function that, based on the address value, defined where it was from and modified it if necessary. However, the overhead expenses it required were enormous. In this case, the solution was purely theoretical, and obviously, unusable for real-world applications, apart from some individual cases.

Implementation (New Approach)

We wished we had modified the addresses during the firmware loading. Of course, it required us to change the program for loading the image into the Flash, as well as to provide additional information about the image itself, but that idea actually sounded plausible. As was said above, the ability to run from any loading address came at a cost of a small increase in code size and slightly lower performance. If we had fixed all bottlenecks directly in the binary image, the relocatability could have been achieved without the aforementioned performance/efficiency losses. There were possible pitfalls, but the idea was worth trying out.

The first method was rough though a promising one. We wondered what if we had made two firmware variants be loaded from different addresses and compared afterwards. Only the addresses should have changed, so we would have seen all the places that needed modification. However, it turned out that there were many more differences than that. Some of them might have been disregarded as irrelevant to our task, but there were no guarantees that we would always be able to distinguish valid issues from artifacts. And in the end, the whole method itself sounded too naive for serious applications.

Taking into consideration the above, it was obvious that we had to change at least some addresses used for global pointers initialization. For simplicity, we supposed that during code generation an intermediate assembler file was created and that we had the ability to intervene with this process. A new idea emerged then. Each time the compiler used a global address for initialization, we could see which address space it used, and if it was from ROM, we could put a label before it.

We put markers before ROM address initialization.

mainMenu:

Reloc2:

.long mainMenuEntriesC

.long mainMenuEntriesM

Reloc3:

.long mainMenuEntriesC+8

At the end of the module, we added a section with a special name and put all those labels in it.

Labels are put into the reloc_patch section:

.section .reloc_patch,"aw",%progbits

.globl _Reloc_3877008883_

_Reloc_3877008883_:

.long Reloc1

.long Reloc2

.long Reloc3

In the linker script, we defined this section as KEEP so it would remain intact, because, obviously, there were no uses of its data. Later, when the executable file was being linked, all the added sections were joined together and the labels got specific values corresponding to the binary image addresses. The key moment here is that those addresses were equal to the offsets in the output file. Therefore, we could locate the places that needed changes. One subtle aspect to be noted, if the initialized data was located in RAM, their initialization would be located in ROM with a known offset. Therefore, we needed two sections: one for ROM and one for RAM data. The first was processed as listed above, while for the addresses of the second section we had to subtract the initial RAM address and add the initialization block offset which was defined in the linker script file.

Then we wrote a small utility program that recovered our sections from the ELF representation and got the offset list for the global addresses.

It shall be noted that there is a simple way to get relocation tables using standard means, i.e. a linker creates sections in ELF when –q opcode is set. These tables contain all the data we retrieved using the described above method and can be used for our purposes as well. However, they are too big, while we aimed at less memory usage. Moreover, we would use only small bits of them; therefore, we would have to deal with a table relocation parsing issue. On the on hand, we would save efforts by leaving compiler as it is, on the other, it would bring up another problem. Thus, we decided in favor of the method described above.

Development of the Approach

That was enough to modify the firmware at load time but we went even further. We defined a simple set of commands, like this one:

’D’ [qty] {data} – write the following qty bytes from the input stream

’A’ [qty] – interpret qty as addresses, add a specific value to them and print them to the output

Send four bytes to the output stream and correct two addresses:

’D’ 0x4 0x62 0x54 0x86 0x12 ’A’ 0x2 0x00001000 0x00001008

If the offset is 0x4000, the result would be like this (for clarity we do not decompose the numbers into bytes):

0x62 0x54 0x86 0x12 0x00005000 0x00005008

Then we turned the initial binary image into a stream of such commands. All data up until the first address that needed modification were skipped without changes, then followed the command that modified one or a couple of addresses, then some data again, and so on, until the end of the file. That way, the information for address correction was embedded into the binary image. On one hand, the resulting file was no longer firmware suitable for booting flashing. But then we were able to process it “on the fly” in streaming mode as we received it, using a small buffer. Thus, we had to modify the loader program a little to change the addresses according to the received commands rather than just writing the input stream into the board Flash/RAM. Moreover, we created an additional utility program that accepted such a file and a starting address as input and then created a firmware.

We went even further. As mentioned above, some addresses were “hardcoded” into the movw, movt instruction pairs. The compiler could tell which of them corresponded to ROM address loading, put labels there and make another section for them. Also, we added a command that chose two words from the stream, interpreted them as loading instruction pairs, retrieved the address, changed it, and then put it back in. Thus, the additional steps during runtime became unnecessary. Apart from that, we got the ability to modify the program at ease (for example, changing the version number, etc.).

This also allowed us to give the program the offset value if necessary. To do that, we created a function with a special name that wrote the constant value to a RAM cell. In code this function started with two movw, movt pairs – the first was to load RAM cell address and the second was for the constant itself.

Retrieving the offset in the RAM cell and r9 register:

int rel_code = 0;

int set_rel_code() {

rel_code = 0x12345678;

return rel_code;

}

void __attribute__((section(".text_init"))) Reset_Handler(void) {

set_rel_code();

asm(“mov r9, r0”);

...

}

We added another stream command that had not been added the offset to the value hardcoded in the load instruction pair, but it actually changed the value to the one being given. As a result, the function put the offset value itself into RAM, and after the function’s call this value was available. All in all, that opened quite a broad range of possibilities, so the additional difficulties look justified.

Current Limitations

Undoubtedly, the need to work with the intermediate assembler file is a flaw of the implementation. It can be neglected because it is hard to say what it exactly affects. Perhaps, we would get rid of it in the future versions by creating labels directly within the compiler’s internal representation. There is also nothing good in that service sections used for retrieving displacements of the binary image, actually take up memory space. However, we could give them fictional addresses where the Flash/RAM is absent as long as there are no errors during loading.

Conclusion

The LLVM compiler was modified to generate binary code that could be tied to any address before loading to the flash memory without using the additional source code or development environment. All the necessary information is contained in the binary code.