apt.llvm.org - moving from physical server to the cloud

In this blog post, I would like to explain how I migrated apt.llvm.org from physical hardware hosted in a datacenter to the Google cloud. This has resulted in better security and faster builds for LLVM Debian/Ubuntu nightly builds.

Previous infrastructure

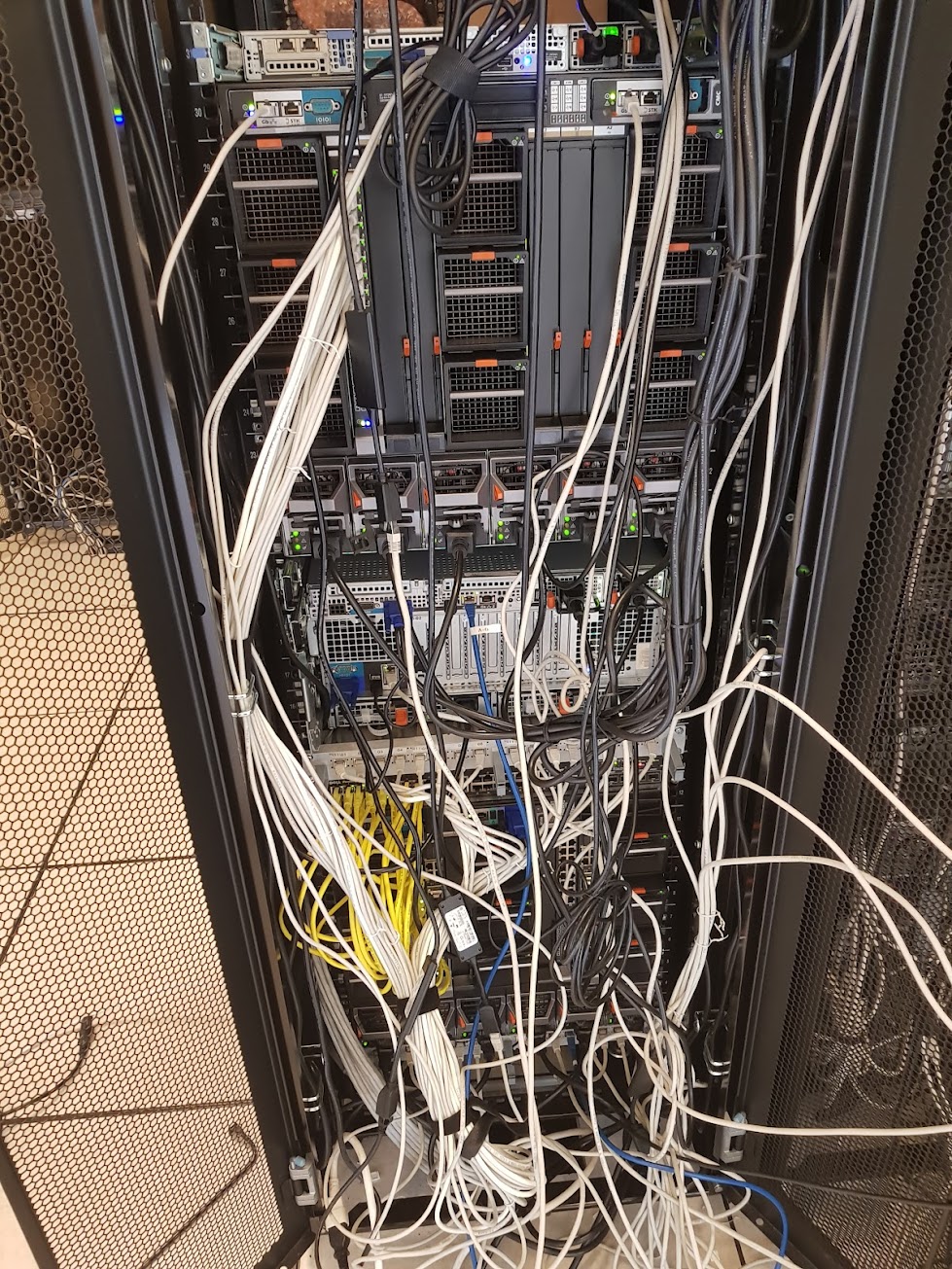

About 10 years ago, Nick Lewycky from Google offered to replace my mix of old and terrible servers with 16 blade servers in a chassis and a control server. Below are pictures of the front and back of these servers, which have served us faithfully for 10 years:

The hosting was sponsored by IRILL, at Inria, next to Versailles.

This setup was running using a PXE install with preseed to set up everything on the 16 blades.

While it served us very well for years, it is now holding us back.

- Some of the blades are dying;

- Old hardware - it takes from 4 to 7 hours per build;

- All blades are always on even if no build is executed;

- Even if it happened rarely, I had to drive to the DC to fix some systems.

New infrastructure

As part of the OpenSSF initiative, Google and the Linux foundation offered a budget to migrate this service on Google Cloud Platform (GCP).

As Jenkins has been working very well, I reused this approach and imported the previous configurations (available on https://github.com/opencollab/llvm-jenkins.debian.net/tree/master/jobs).

I followed most of the tutorial provided on GCP, Using Jenkins for distributed builds on Compute Engine.

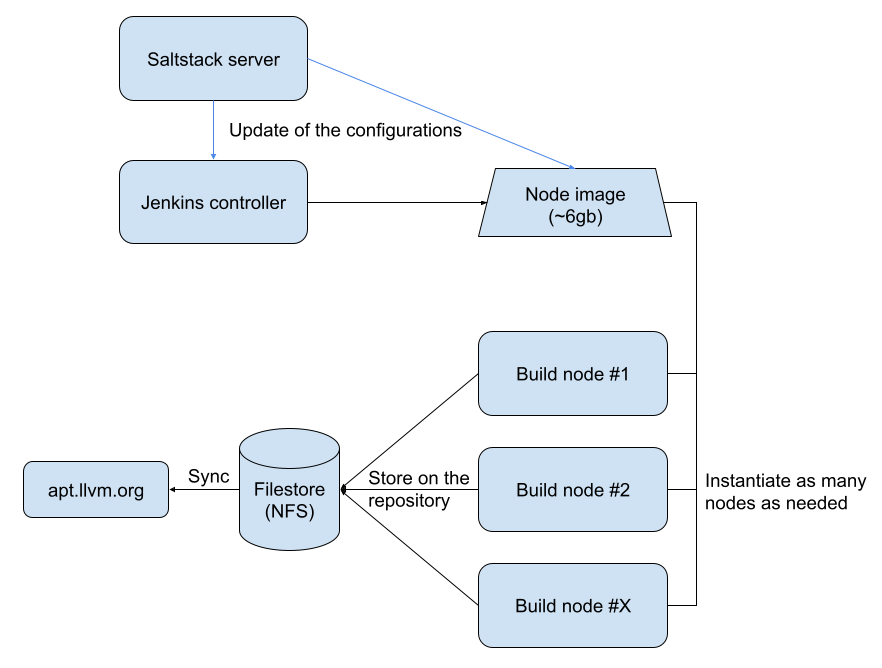

The architecture is the following:

Similar to puppet or chef, Salt is the configuration management tool used to configure the various systems. A salt server configures both the Jenkins controller and the reference node. This node is a preconfigured VM with all the dependencies and tools to start the build. This node is halted most of the time and only started when the image needs to be updated.

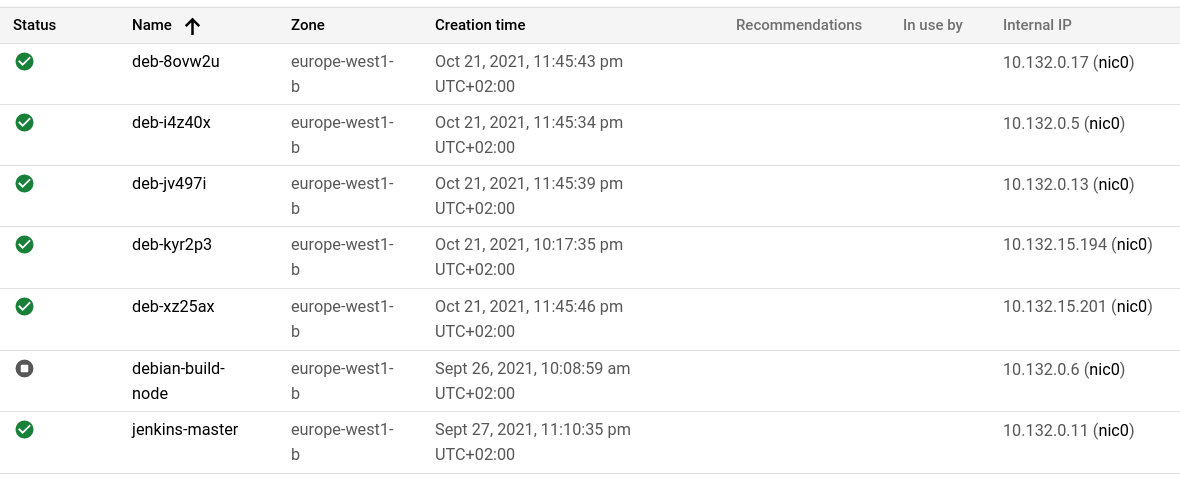

For example, the list of Virtual Machines now usually looks like the following screenshot:

- 5 build VMs - off after 5 minutes without activity

- The template VM (off as it is only started to update the image)

- The jenkins orchestrator

Build servers

The controller is always on and starts/ends the build nodes.

The reference node is configured and updated using this script, based on gcloud, the Google cloud CLI:

https://github.com/opencollab/llvm-jenkins.debian.net/blob/master/image-update.sh

This script performs the following steps:

- starts the reference node and then ssh into it.

- Perform the needed changes (ex: new chroot for a new distro version, new build hooks, etc).

- Once the changes are performed.

Usually:

- Salt update

- Refresh the chroots

- git pull llvm-project

- Stops the VM

- Creates a new image.

- Archives the old image.

- This image will be used by Jenkins to start new VMs.

The node image contains the various i386 and amd64 chroot for supported Debian and Ubuntu installs. The LLVM repository is also checked out to avoid doing a long clone with many files on every VM startup.

Thanks to this, the jobs just need to perform a small git pull instead of a full clone.

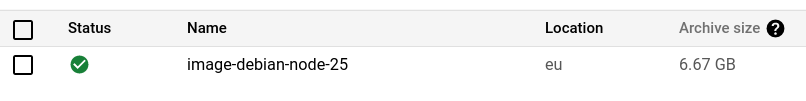

The size of this image is 6.67gb. This approach saves about 10 minutes of the build pipeline (skipping the creation of the chroot + full clone).

This wasn’t easy. I had to iterate 25 times to have a proper image supporting all the use cases.

GCP provides a shared file system mechanism available as an NFS mountage called Filestore. Each build node has access to it and will update the various repositories just like if it was a local file system.

Benefits and cost

The first benefit is security. This is based on the Google cloud infrastructure, so it benefits from all their security work.

The fact that the VMs are always cycled and recreated from a clean image will also help. They are not directly accessible from the Internet (they leverage cloud NAT to be able to download packages from the Internet), so it will be harder to attack.

An amd64 build now runs in parallel takes **about 50 minutes **instead of almost 7 hours.

In terms of cost, depending on the activity, the daily cost varies from 70 to 150 US$/day.

Now that the migration has been completed, it is now possible to consider some builds leveraging PGO and LTO for faster binaries.

Thanks

Thanks to Laurent Vaylet from the GCP team for the help and patience answering my newbie questions, and also thanks to Google and the Linux Foundation for the GCP credits and support.