GSoC 2025: Improving Core Clang-Doc Functionality

I was selected as a contributor for GSoC 2025 under the project “Improving Core Clang-Doc Functionality” for LLVM. My mentors for the project were Paul Kirth and Petr Hosek.

Clang-Doc is a tool in clang-tools-extra that generates documentation from Clang’s AST and can output Markdown, HTML, YAML, and JSON. The project started in 2018 but major development eventually slowed. Recently, there have been efforts to get it back on track.

This year, the GSoC project idea had a simple premise: improve core functionality.

The Project

The project idea proposed three main areas of focus to improve documentation quality.

- C++ support

- Doxygen comments

- Markdown support

First, not all C++ constructs were supported, like friends or concepts. Not supporting core C++ constructs in C++ documentation is not good. Second, it’s important that Doxygen command support is robust and that we can support as many as possible. Lastly, having Markdown available to developers for documentation would be useful. Markdown provides the power of expression in an area that is technically dense. It can be used to highlight critical information and warnings.

The Architecture

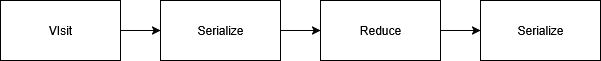

Here’s a quick overview on Clang-Doc’s architecture, which follows a map-reduce pattern:

- Visit source declarations via Clang’s

ASTVisitor. - Serialize relevant source information into an

Info(Clang-Doc’s main data entity). - Write

Infos into bitcode, reduce, and reread. - Serialize

Infos into the desired format with a target backend.

The architecture seems straightforward at a glance, but Clang-Doc has critical flaws at step 4.

The Bad

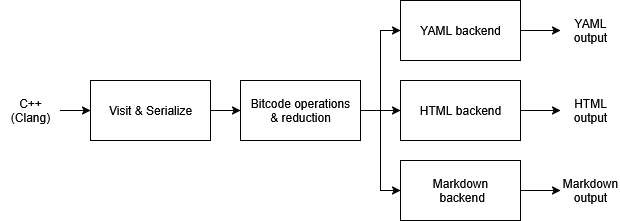

Clang-Doc has support for many formats. That sounds great in principal, but the backend pipeline’s execution made development extremely cumbersome.

Unlike in LLVM, Clang-Doc doesn’t have a framework like CodeGen that shares functionality across different targets.

To document a class, every backend needs to independently implement logic to serialize the class into its target format.

Each backend also has separate logic to write all of the documented entities to disk.

There is also no IR where Infos can be preprocessed, which means that any organizational preprocessing done in a backend can’t be shared.

Here’s the code for serializing the bases and virtual bases of a class in the HTML backend:

std::vector<std::unique_ptr<HTMLNode>> Parents =

genReferenceList(I.Parents, I.Path);

std::vector<std::unique_ptr<HTMLNode>> VParents =

genReferenceList(I.VirtualParents, I.Path);

if (!Parents.empty() || !VParents.empty()) {

Out.emplace_back(std::make_unique<TagNode>(HTMLTag::TAG_P));

auto &PBody = Out.back();

PBody->Children.emplace_back(std::make_unique<TextNode>("Inherits from "));

if (Parents.empty())

appendVector(std::move(VParents), PBody->Children);

...

Here’s the same logic for doing it in Markdown:

std::string Parents = genReferenceList(I.Parents);

std::string VParents = genReferenceList(I.VirtualParents);

if (!Parents.empty() || !VParents.empty()) {

if (Parents.empty())

writeLine("Inherits from " + VParents, OS);

else if (VParents.empty())

writeLine("Inherits from " + Parents, OS);

else

writeLine("Inherits from " + Parents + ", " + VParents, OS);

writeNewLine(OS);

}

...

You can see how differently both backends need to handle these constructs, which makes it complicated to bring feature parity. The HTML tag creation being so tightly coupled to the documentation serialization also highlights a different problem of formatting problems being difficult to identify.

This lack of generic handling imposed a very high maintenance cost for extending basic functionality. It also easily led to backend disparity; a construct might be serialized in YAML, but not in Markdown. Changes to how a documentation entity was handled would not be uniform across backends.

Testing was also in an awkward spot. If not all backends were guaranteed to generate the same documentation, who could be trusted as the source of truth? YAML was originally meant to serve this role, but it suffered from feature disparity. It’s a cumbersome process to implement support for a construct in YAML, verify it there, but then also go to implement it in HTML. There’s a logical disconnect: what’s serialized in YAML isn’t guaranteed to reflect in HTML, so what is the benefit of updating YAML if my documentation is shown through HTML?

The Good

The good news is that Clang-Doc’s recent improvements had brought in changes that could rectify these problems, with a bit more work. Last year’s GSoC brought in great improvements that became the basis of my summer. First, last year’s GSoC contributor landed a large performance improvement. I might not have been able to test Clang-Doc on Clang itself without it.

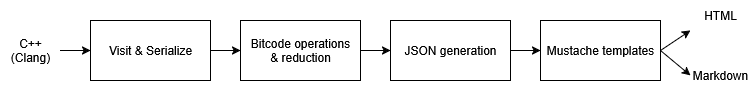

The same contributor authored the Mustache template engine implementation in LLVM. Mustache templates allow Clang-Doc to shift away from manually generating HTML tags and eliminate high maintenance burdens. Templates could also solve the feature parity problem by using JSON to feed templates. This was a huge part of my summer and allowed me to bring in great improvements that would make Clang-Doc more flexible and easier to contribute to.

Building a JSON Backend

While studying the codebase during the Community Bonding Period, I determined that creating a separate JSON backend would be extremely helpful. A JSON backend presented two immediate benefits:

- We could use it to feed our Mustache HTML templates and future template usage.

- As the main feeder format, testing can be focused on the JSON output.

The existing Mustache backend in Clang-Doc already contained logic to create JSON documents, but they were immediately discarded when the templates were rendered. This backend is extremely beneficial to Clang-Doc because it completely eliminated any need for manual HTML tag generation, thus greatly reducing lines of code. If the JSON and template rendering logic from the existing implementation were uncoupled, we could apply the same pattern to any format we’d want to support. Markdown generation would be a similar case where templates would be used to automate the creation of all markup syntax.

This diagram models the architecture that Clang-Doc would follow given a unified JSON backend. Note the similarities to Clang, where our frontend (the visitation/serialization) gathers all the information we need and emits an intermediate representation (JSON). The JSON is then fed to the desired templates to produce our documentation, similar to how IR is used for different LLVM backends. Following this pattern would reduce the maintenance to only the JSON generation; all the formatting for HTML, Markdown, etc. would exist in template files that are very simple to change and neatly separates documentation logic from display/formatting logic. Also note how much more streamlined it is compared to the previous diagram where serialization logic was separated among Clang-Doc’s backends.

Thus, I adapted the JSON logic from the Mustache backend and create a separate JSON backend. I also added tests to ensure the C++ constructs that Clang-Doc already supported were properly serialized in JSON. I didn’t realize it at the time, but this would end up dramatically accelerating my pace of implementation. I was especially pleased with the timeframe of this feature since I had no plans at all to work on it when submitting my proposal.

C++ Language Support and Testing

After landing the JSON generator in about a week, I returned to my proposed schedule by implementing support for missing C++ constructs. The new JSON generator allowed me to quickly implement and test these features because I didn’t have to worry about HTML formatting or appearance. I could work with the assumption that as long as the information was properly serialized into JSON, it would be able to be displayed well in HTML later.

Testing is an area that the JSON backend brought a lot of clarity to. Clang-Doc didn’t have a format where all the information we wanted to document was validated. At one time, YAML was meant to be that format, but it suffered from feature disparity since it wasn’t relevant when something needed to be displayed in HTML. If we used HTML instead, there was a lot of other data (tags, indentation, classes, IDs) that would need to be validated alongside the construct. Testing the documentation and testing the displayed content are two different tasks. I ended up adding 14 different test files over the course of the summer to ensure test coverage.

Pull Requests

- add tags to Mustache namespace template

- add a JSON generator

- add namespaces to JSON generator

- removed default label on some switches

- precommit and add support for concepts

- precommit and document global variables

- serialize isBuiltIn and IsTemplate

- precommit and serialize friends

Comments

Groups and Order

Comments weren’t ordered in Clang-Doc’s HTML documentation. They were just displayed in whatever order they were serialized in, which is the order that they’re written in source. This meant comments would be extremely difficult to read - you don’t want to search for another parameter comment after reading the first one, even if they’re expected to be written in order in source.

Funnily enough, Mustache made this a little more complicated.

The only logic operation that Mustache has to check if a field exists is an iteration like {{#Fields}}, but any header that denotes a comment section would be duplicated.

{{#Fields}}

<h3>Field Header</h3>

{{FieldInfo}}

{{/Fields}}

the <h3> header would be duplicated for every iteration over Fields.

If the header was outside of the iteration, then it would be displayed even if there weren’t any elements in Fields.

All of the logic to order them needs to be done in the serialization to JSON itself, so I had overhaul our comment organization.

Previously, Clang-Doc’s comments were organized exactly as in Clang’s AST like the following:

FullCommentBriefCommentParagraphCommentTextCommentTextComment

BriefCommentParagraphComment

Everything was unnecessarily nested under a FullComment, and TextComments were also unnecessarily nested.

Every non-verbatim comment’s text was held in one ParagraphComment.

Since there was only one, we could reduce some boilerplate by directly mapping to the array of TextComments.

After the change, Clang-Doc’s comments were structured like this:

BriefCommentsTextCommentArrayTextCommentArray

ParagraphCommentsTextCommentArray

Now, we can just iterate over every type of comment, which means iterating over every array. This left our JSON documentation with a few more fields, since one is needed for every Doxygen command, but with easier identification of what comments exist in the documentation. After this refactor was landed, I implemented support for the comments we had already supported and ones we didn’t, like Doxygen code comments.

Reaping the benefits of JSON

This was an area where the JSON backend really accelerated my progress. Without it, I would’ve written the same JSON logic but written tests for HTML output. This meant that I would’ve had to:

- Add the appropriate templating language to allow the comments to render.

- Add the correct HTML tags to allow the test to pass.

As I mentioned, comments weren’t being generated the best in HTML anyways, so I could’ve run into more annoyances if I had to follow that workflow. Instead, I could just write some really simple JSON.

Pull Requests

Here are the pull requests I made during this phase of the project:

- add namespace references to VarInfo

- fix ASan complaints from passing RepositoryURL as reference

- integrate JSON as the source for Mustache templates

- separate comments into categories

- enable comments in class templates

- remove nesting of text comments inside paragraphs

- generate comments for functions

- add param comments to comment template

- add return comments to comment template

- add code comments to comment template

Markdown

Markdown was the most speculative aspect of the project. It wasn’t clear whether we’d try to integrate a solution into Clang itself or whether we’d keep it in clang-tools-extra.

A JavaScript Solution

The first option I explored was suggested by my mentor, which was a JavaScript library called Markdown-Tag. This would’ve been really convenient since all it requires is an HTML tag to enable rendering, so any comment text in a template can be easily rendered. Unfortunately, it requires all HTML to be sanitized, which defeats the purpose of a ready-made solution for us. We would have to parse any potential HTML in comments anyways.

A Parser Solution

Without an out-of-the-box solution, we were left with implementing our own parser. When I considered this in my proposal, I knew an in-tree parser would want to conform to the simplest possible standard. Markdown has no official standard, so I opted for CommonMark conformance.

The summer ended without a complete solution since a couple weeks were spent researching whether or not this could be integrated directly in the Clang comment parser or whether we’d need to build our own solution or not. You can see my initial draft here. I plan to continue working on this parser and landing it in Clang-Doc.

Refactors, Name Mangling, and More!

During my summer, I would stumble into places where I would think “This could be better” and my mentors usually agreed. Thus, there were a few patches where I dedicated time to general refactors to improve code reuse and hopefully make the lives of future contributors much easier than what I had to go through. In fact, one of my best refactors was of the JSON generator that I wrote, which my mentor noted had a lot of areas for great code reuse. Future me was extremely thankful for the easy-to-use functions I had added.

Bitcode Refactor

The bitcode read/write operations contain highly repetitive code.

Adding something to documentation, like serializing const for a function, required several copy-pastes in several locations.

It was structured like so:

case BI_MEMBER_TYPE_BLOCK_ID: {

MemberTypeInfo TI;

if (auto Err = readBlock(ID, &TI))

return Err;

if (auto Err = addTypeInfo(I, std::move(TI)))

return Err;

return llvm::Error::success();

}

addTypeInfo is specific for MemberTypeInfo, so every other type of Info would need to call its own function.

Hence, highly repetitive similar code.

I refactored that block to this:

return handleTypeSubBlock<TypeInfo>(ID, I, CreateAddFunc(addTypeInfo<T, TypeInfo>));

handleTypeSubBlock contains the same logic as the previous block, but it calls a generic Function.

All of this was achieved without compromising the performance of documentation generation.

Mangling Filenames

Clang-Doc had a bug stemming from non-unique filenames. The YAML backend avoided this problem because its filenames were SymbolIDs, but this meant that the lit tests would have to use regex to find the file for FileCheck. Nasty.

In HTML and JSON, the filenames for classes were just the class name.

If you had a template specialization, this would cause problems

In HTML, we’d get duplicate HTML resulting in wonky web pages.

In JSON, we’d get a fatal error from the JSON parser since there were two sets of top level braces.

I used ItaniumMangleContext to generate mangled names we could use for the filenames.

Pull Requests

Here are the pull requests I made for refactors during the project:

- Serialize record files with mangled name

- refactor BitcodeReader::readSubBlock

- refactor JSONGenerator array usage

- refactor JSON for better Mustache compatibility

Overview

- I implemented a new JSON generator that will serve as the basis for Clang-Doc’s documentation generation. This will vastly reduce overall lines of code and maintenance burdens.

- I added a lot of tests to increase code coverage and ensure we are serializing all the information necessary for high-quality documentation.

- I refactored our comment handling to streamline the logic that handles them and for better output in the HTML.

- I also explored options for rendering Markdown and began an implementation for a parser that I plan on working on in the future.

- Along the way, I also did some refactoring to improve code reuse and improved maintenance burdens by reducing boilerplate code.

After my work this summer, Clang-Doc is nearly ready to switch to HTML generation via Mustache templates, which will be a huge milestone. It is backed by the JSON generator which will allow for a much more flexible architecture that will change how we generate other documentation formats like our existing Markdown backend. All of this was achieved without compromising the performance of documentation generation. I also hope that future contributors have an easier time than I did learning about and working with Clang-Doc. The threshold for contributing was high due to a disjointed architecture.

I’m also very excited to present my work and showcase Clang-Doc at this year’s LLVM Dev Meeting during a technical talk. This is the first time I’ll be presenting at a conference and I didn’t expect to have the opportunity when I started at the beginning of the summer.

Over the summer, I addressed these issues:

- template operator T() produces a bad name

- Add a JSON backend to clang-doc to better leverage mustache templates

- Reconsider use of enum InfoType::IT_default

- Add a JSON backend to clang-doc to better leverage mustache templates

Future Work

These are issues that I identified over the summer that I wasn’t able to address but would benefit from community discussion and contribution.

Doxygen Grouping

Doxygen has a very useful grouping feature that allows structures to be grouped under a custom heading or on separate pages. You can see it in llvm::sys::path. We opened up an issue for Clang to track this issue, which ended up being a duplicate of this issue.

There would most likely have to be some major changes to Clang’s comment parsing and Clang’s own parsing. That’s because a lot of the group opening tokens in Clang are free-floating, like so:

/// @{

class Foo {};

That @{ doesn’t attach to a Decl; only comments directly above a declaration are attached to a Decl in the AST.

My mentors wisely advised that this would be too much to even consider this summer, and could probably be its own GSoC project.

Cross-referencing

In Doxygen you can use the @copydoc command to copy the documentation from one entity to another.

Doxygen also displays where an entity is referenced, like where a function is invoked.

Clang-Doc currently has no support for this kind of behavior.

Clang-Doc would need a preprocessing step where any reference to another entity is identified and then resolved somewhere.

One of my mentors pointed out that it would be great to do during the reduction step where every Info is being visited anyways.

This actually wasn’t something I had even considered in my proposal besides identifying that @copydoc wasn’t supported by the comment parser.

It’s a common feature of modern documentation, so hopefully someday soon Clang-Doc can acquire it.

Acknowledgements

Thank you very much to my mentors Paul Kirth and Petr Hosek for guiding me and advising me in this project. I learned so much from review feedback and our conversations. I would not be presenting at the Dev Meeting if not for the encouragement you both gave.